Jim Murray never had to claim he was the greatest sportswriter of them all. Others did it for him. He was named national sportswriter of the year 14 times, including 12 years in a row. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame and won a Pulitzer Prize for commentary. Perhaps most impressive, he did everything without ego or pretension.

“In press boxes Murray would mumble and fuss that he had no angle, sigh heavily and then, when he had finished his column, no matter how good it was, he would always slide back in his chair and say, ‘Well, fooled ’em again,’ ” Rick Reilly wrote in a 1986 Sports Illustrated profile of Murray titled “King of the Sports Page.”

Murray was the undisputed king. And it’s not even close. He was Rocky Marciano in a ring, Bobby Fischer at the U.S. Chess Championship, Wilt Chamberlain scoring 100, Secretariat at the Belmont, Bo Jackson on Monday night, Tiger Woods at Augusta and the 1996 Chicago Bulls. All rolled into one prolific, profound sportswriter.

Murray had a 55-year career in journalism that started as a police and federal beat reporter at the New Haven (Connecticut) Register in 1943 and ended as a Los Angeles Times sports columnist in 1998. Along the way, he worked as a general assignment and rewrite man at the Los Angeles Examiner, covered Hollywood for Time Magazine, launched Sports Illustrated and was one of SI’s original writers.

Starting in 1961, Jim Murray wrote four columns a week, every week, for 27 years at the Los Angeles Times. His columns were nationally syndicated in more than 150 newspapers. He was a man of his words. We collected some for you to read.

On How Expansion Changed Baseball

Los Angeles Dodgers right-hander Don Drysdale fires the first pitch to New York Yankees batter Tony Kubek to open Game 3 of the 1963 World Series at Dodger Stadium. AP Photo

Column: Baseball Dying Out and Real Estate Has Hand in the Killing

Publication date: Sept. 11, 1963

Murray’s words: The home run, the stroke that saved baseball after the Black Sox Scandal, is becoming as rare as the great plains bison. Like all things that made America strong, it is being replaced by obsolescences like drag bunts. The game is full of gray eminences like the Cleveland Indians who pass through town like fog and are about as exciting as warts. The game needs Babe Ruth and it gets relief pitchers. Atomic physics is no more abstruse than the Baltimore roster. Hardly a man is now alive who can tell you right off the bat who their right fielder is. Not even a bubblegum collector can recall the name of the Boston catcher. The Yankees lead the rest of the league around so docilely that they should have rings in their noses.

… Baseball has moved out of bandboxes and into landing strips.

… So I say, bring in the fences, Walter [O’Malley]. Nothing is duller than the last half of the 9th inning in a 6-1 game with the home heroes trailing and you know nothing less than a court order is going to let them get five runs. Bring a look of fear and a feel of sweat (even on a cold night) back to the pitcher. The home run is the fun of baseball, not the bunt. Let’s bring it back before the game gets as dull as dancing school.

Bottom line: The early 1960s were a period of change for the national pastime as Major League Baseball went from 16 to 20 teams.

The Washington Senators and Los Angeles Angels joined the American League in 1961, while the old Senators moved to Minneapolis-St. Paul and became the Minnesota Twins. A year later, the National League welcomed the Houston Colt .45s (renamed Astros) and New York Mets.

With new teams and bigger stadiums like Candlestick Park (opened in 1960 by the San Francisco Giants) and Dodger Stadium (opened by Los Angeles Dodgers in 1962), players, teams and fans needed some time to adjust to the game’s new geography and geometry.

On the 1965 World Series

Los Angeles Dodgers southpaw Sandy Koufax delivers against the Minnesota Twins in Game 2 of the 1965 World Series at Metropolitan Stadium in Minneapolis-St. Paul. AP Photo

Column: Twins Are Game (Fair, and Dead)

Publication date: Oct. 12, 1965

Murray’s words: Minnesota’s best hope now would appear to be snow. If the Dodgers have to put on chains, they might not be able to make second base on a crawl like a sniper pushing through the jungle brush but if the Dodgers get on base, the Minnesota players get to know what Custer felt like. Like he wishes he studied all those footprints better before he got surrounded by the guys who made them. There are Dodgers who go around them so fast the Twins never do catch the numbers. The way the Dodgers play, they’ll have to change the name of this game to “football.”

Bottom line: Jim Murray could deliver one-liners as well as any vaudeville comedian and turned his Game 5 commentary into a Bob Hope roast. (Hope even represented Murray at an awards dinner he couldn’t attend one year.) The Dodgers beat the Twins 7-0 at Dodger Stadium to take a 3-2 series lead. The series returned to Minnesota, where the Twins won Game 6. Then, Sandy Koufax pitched a 2-0, three-hit, 10-strikeout, complete-game shutout in Game 7, his third start in eight days, to clinch the title in a performance that was no joke.

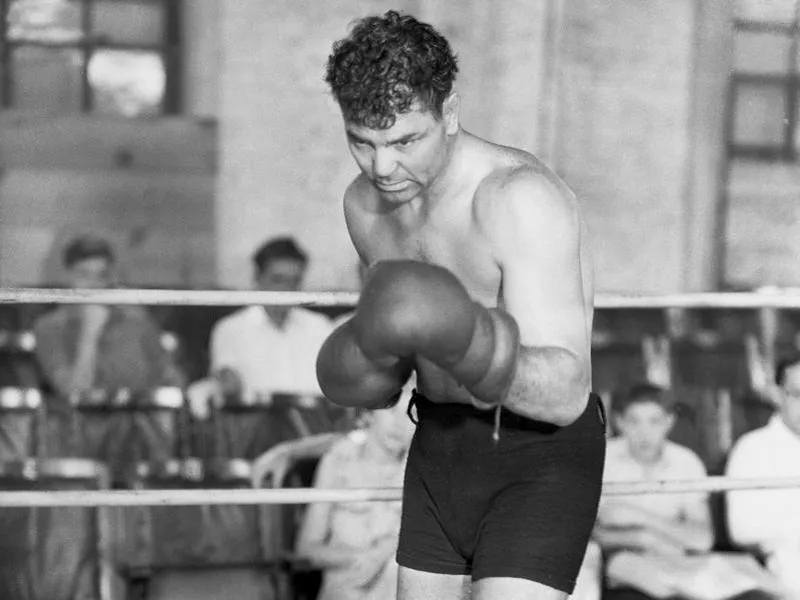

On Jack Dempsey

Jack Dempsey training in Reno, Nev., in 1931. AP Photo

Column: Dempsey Was the Meanest

Publication date: Nov. 17, 1965

Murray’s words: Jack Dempsey was the only champion who practiced the same way the early Christians did — as if his opponent had a mane and claws and would not only fight him but eat him. Dempsey even fought a punching bag as if it might open fire at any time. Sparring partners limped out of town on every bus. A newspaper man climbed into the ring with him once as a gag, and a colleague had to write the fellow’s story for a few days afterwards while he took nourishment through a straw. “Dempsey fought you,” a battered spar-mate once confided, “as if the two of you were on a ledge 20 stories up and it was either him or you.”

Bottom line: Jack Dempsey became a heavyweight hero and cultural icon during the Roaring ’20s. Due to his overwhelming popularity and power, the facts about him often were hard to distinguish from the legends. That’s how bad (meaning good) he was.

On the Evolution of Boxing

Muhammad Ali covered his mouth with tape as a gag on his way to the weigh-in scales at Madison Square Garden for his 1963 fight against Doug Jones in New York. AP Photo

Column: Dempsey Admits Boxing Is Dead

Publication date: Jan. 14, 1966

Murray’s words: As far as I’m concerned, Cassius Clay should be a silent movie. He and his gang may “own” the heavyweight championship. But they better check its pulse before they throw a party. As the old desert proverb goes, you won’t ride far on a dead camel — or a boat with a hole in it. And you won’t make anybody feel especially good when they rent it to you 40 years from now either.

Bottom line: Cassius Clay converted to Islam in 1961 and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. He was dominating the fight game. But it wasn’t easy to convert everyone into a fan.

Some people, like Murray, preferred the days of Dempsey and worried about the future of the sport. Boxing survived. And years later, Ali hailed Murray as “the greatest sportswriter of all time.”

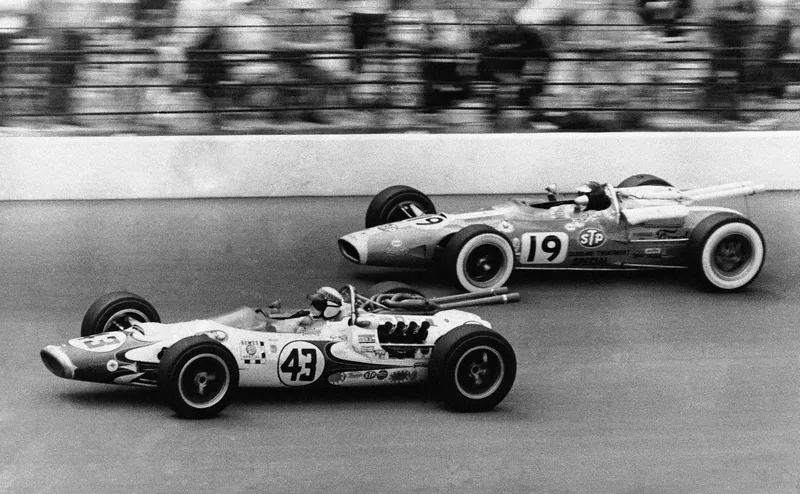

On the Indianapolis 500 and Auto Racing

Jackie Stewart (43), left, and Jimmy Clark battle down the homestretch in the 1966 Indianapolis 500. AP Photo

Headline: Gentleman, Start Your Coffins!

Publication date: May 29, 1966

Murray’s words: Indy, in short, is just a proving ground for a lot of stock 1966 Lola Fords, and we take you now to the Speedway where the announcer is explaining the new rules to the crowd. … “Now, ordinarily, for test like these, automotive research uses articulated dummies to study crash effects, but today instead of articulated dummies we’re using race drivers. Gentlemen, start your coffins.”

Bottom line: Speed thrills — and kills. Seventy-three individuals have died at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway since 1909, including 13 since Murray wrote his four famous words.

Thoughout his career, Murray used sarcasm and gallows humor to engage his audience. “I find most people hate to be informed,” he said. “People need to be amused, shocked … or angered.”

On Water Skiing

Barefooted water skiers, in costumes, skim over the water in an aqua ballet during a performance of a “Marine Circus” at the new Marine Stadium at Jones Beach, Long Island, N.Y., in 1952. The performers include champion water skiers. Ed Ford / AP Photo

Column: Water Skiers Risk Life, Limb in Championships

Publication date: June 15, 1966

Murray’s take: Water skiing is a sport which falls some place between playing golf in a thunderstorm and probing a lion for a sore tooth. … It’s a sport practiced 70% by women. There are several reasons for this. First, it’s good for the figure. Second, it keeps you from getting old. Of course, so does suicide.

Bottom line: When was the last time you read anything about water skiing? Coming up with dozens of column ideas a year requires some creativity. Jim Murray was a master at noticing things others didn’t and could make a game of tiddlywinks seem like a spy thriller with laughs.

On Vince Lombardi Going to the Washington Redskins

Washington Redskins head coach Vince Lombardi voices his opinion about a play during the team’s regular-season debut against the New Orleans Saints in New Orleans, La., in 1969. AP Photo

Column: Vince Could Help Nation

Publication date: March 1, 1969

Murray’s words: He probably would have preferred New York, but I, for one, am glad Mr. Lombardi goes to Washington. His mere presence should have a salutary effect on that effete-society. I wish the foreign diplomatic corps could take up pro football so they could sense the raw toughness of America as typified by this granitic citizen from Brooklyn, part Latin scholar, part riffian, part pedagogue, part pirate, part poet, part truck driver, part temperament, part sentiment — all man. There are more like him in this country than the striped-pants type they get to see in Washington.

Bottom line: Vince Lombardi left Green Bay in 1968 to lead the Washington Redskins as coach and general manger. After his first season in the nation’s capital, Lombardi was diagnosed with terminal cancer and died on Sept. 3, 1970, at the age of 57.

Following his death, the NFL Super Bowl trophy was named after him.

Lombardi regretted he did not have time to accomplish more in his life. Who knows? Maybe he could have gotten the Washington political crowd to understand the true meaning of teamwork.

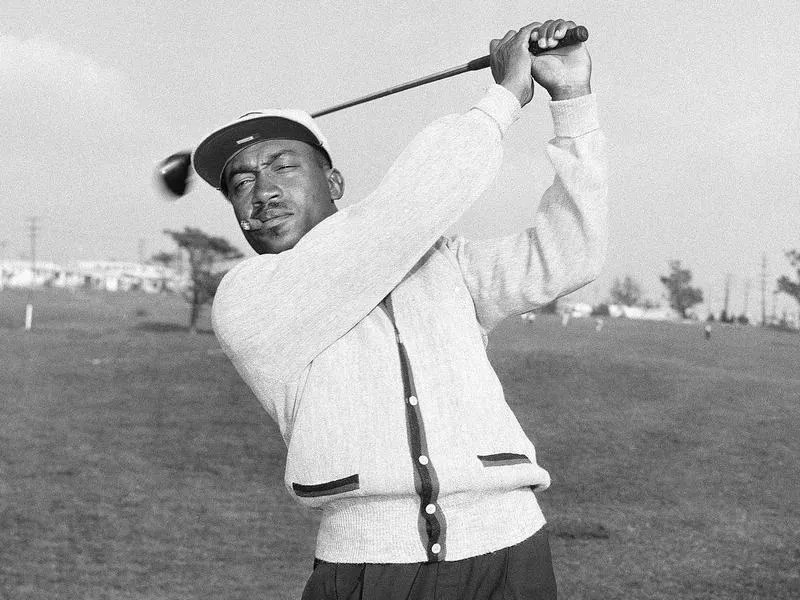

On Racism at the Masters

Charlie Sifford works out at the Western Avenue golf course in Los Angeles in 1957. Harold P. Matosian / AP Photo

Column: As White as the Ku Klux Klan

Publication date: April 6, 1969

Murray’s words: OK, rest easy, Jefferson Davis! Put down the gun, John Wilkes Booth. Let’s hear a chorus of Dee-eye-exeye-eee! Run up with the Stars and Bars. You won’t have to blindfold that Confederate general’s statue after all. Downtown Tobacco Road is still safe from the 20th century.

The Masters golf tournament is as white as the Ku Klux Klan. Everybody in it can ride in the front of the bus.

There’s nothing the Supreme Court can do about it. Integration fell about 18 strokes or 20 Masters points short. Integration missed the cut.

Bottom line: Charlie Sifford was a great golfer in the 1950s. He also was black. The PGA was for whites only until 1961, so Sifford wasn’t allowed to play until he was almost 40.

The Greater Greensboro Open was Sifford’s last chance to qualify for the Masters. Sifford did not make the cut. “Now they can keep their tournament down there lily-white,” he told Murray.

“Wait a minute, Charlie!” Murray concluded. “You forgot the caddies.”

On Peggy Fleming’s Toughness

Peggy Fleming performs at the 1968 U.S. Women’s Figure Skating Championship in Philadelphia, Pa. Fleming, 19, won her fifth national title and also captured a spot on the U.S. Olympic team for the Winter Olympic Games in France. AP Photo

Column: Peggy’s No Rowdy Hero

Publication date: July 18, 1972

Murray’s words: Peggy Fleming doesn’t look tough enough to beat the world in anything. She looks if she sat on a veranda or under a parasol her whole life, and would need smelling salts if she saw a bug.

But she’s as tough as Joe Frazier. Never mind the clear white beauty of the skin, the perfection of the figure, the beauty on ice that makes her look like something off a Bavarian wedding cake or gingerbread cookie.

You would think, to look at her, she arrived in the company of seven dwarfs. But Peggy Fleming was as fierce a campaigner as an NFL fullback. Figure skating is as demanding as linebacking. The scars are where they don’t show.

Bottom line: Murray was way ahead of his time. In the good ol’ boys club of sports, he championed equal rights and greatness regardless of gender, race or class. And he did so with humor and grace.

Even though Title IX passed in June 1972 to prohibit discrimination based on gender in athletics and academics, comparing figure skating to football in the early 1970s was a bold and progressive statement.

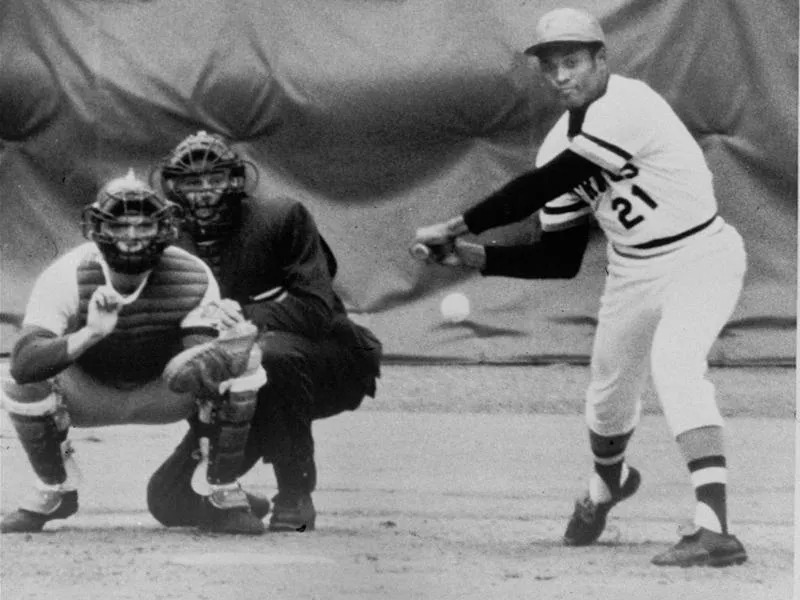

On Roberto Clemente’s Death

Pirates right fielder Roberto Clemente gets his 3,000th hit in 1972, off Mets pitcher Jon Matlack, during a game in Pittsburgh. AP Photo

Column: I Remember Roberto

Publication date: Jan. 8, 1973

Murray’s words: Old Aches and Pains, we called him around the press room. Here was a guy, you could drive railroad spikes with. You could scratch a match on his stomach. He wasn’t born, he was mined. He was the healthiest specimen I ever seen in my life. He didn’t have a pimple on him. The eyes were clear. I never even heard of him having to blow his nose. Yet, he was positive he was terminal. You’d get the idea reports of his birth were greatly exaggerated.

Bottom line: Only the good die young. Roberto Clemente was 38 when he died in a plane crash delivering aid to earthquake victims in Nicaragua.

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973 — the first Latin American and Caribbean player enshrined — and was as good as it gets.

As Greek historian Herodotus wrote, “Whom the gods love dies young.” The baseball gods must have wanted Clemente’s bat, glove and arm.

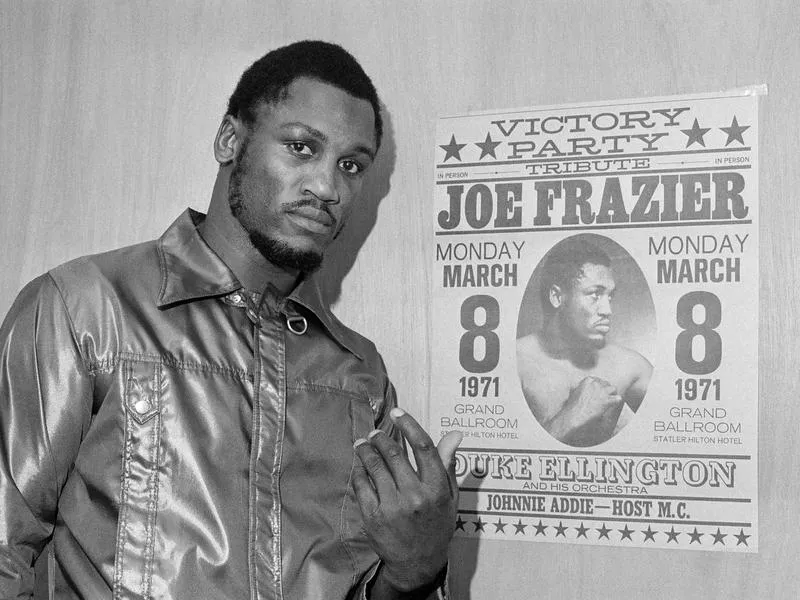

On Joe Frazier

Heavyweight champ Joe Frazier leaves his dressing room after a final public workout in Philadelphia on March 6, 1971, before his title defense bout with Muhammad Ali in New York. Bill Ingraham / AP Photo

Column: And Still Champion!

Publication date: Jan. 24, 1975

Murray’s words: They say Joe never made change for a bill in his life. If all he had was a $100, the cabby — or the shoeshine boy — got it. There’s $10 million of Joe Louis money lying around the country, some place where we can all get a shot at it, because Joe never stuck it in a numbered account in Switzerland. He stuck it in the palms of hat-check girls, bellhops, panhandlers, golf hustlers, widows and waiters. He did everything but throw it off balconies. What his pals didn’t take, the government did. All Joe Louis has left is friends. The only guy he ever hurt outside the ring was himself.

Bottom line: Humble stars were some of Murray’s favorite because he was modest himself. He once said that he didn’t deserve a Pulitzer Prize because “you should get a Pulitzer for discussing more cosmic events than Dodgers versus the Braves.”

After winning the Pulitzer in 1990 — joining Arthur Daley (1956), Red Smith (1976) and Dave Anderson (1981) as the only other sports columnists to win Pulitzers — Murray displayed his typical self-deprecation.

“I never thought you could win a Pulitzer just for quoting Tommy Lasorda correctly,” he said.

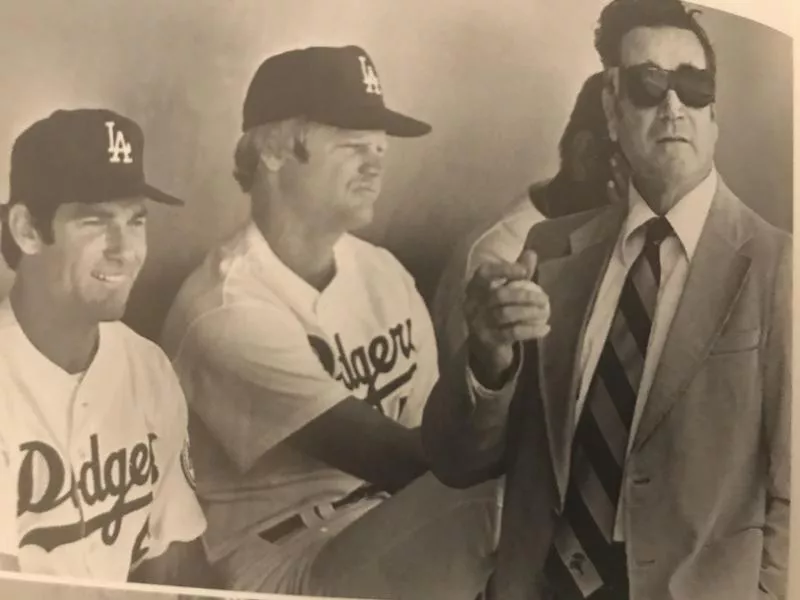

On Walter Alston’s Retirement

Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, left, hugs manager Walter Alston at Yankee Stadium after the Dodgers beat the Yankees to win the 1955 World Series. AP Photo

Column: Murray Bids Alston a Fond Farewell

Publication date: Oct. 8, 1976

Murray’s words: I used to laugh when someone would say, ‘Why shouldn’t Alston win with all that talent?’ and I’d say, ‘Yeah. Too bad he doesn’t have some better baseball players to go with that talent.’ I think you ran that wild animal act that was the Dodgers about as well as it could be run without a whip and a chair.

Bottom line: Good luck finding a foul word about Walter Alston. Anywhere. He was the consummate professional and a compassionate human being.

He managed the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers on one-year contracts for 23 seasons from 1954 to 1976, winning 2,040 games and four World Series.

During the offseason, he taught high school science, biology, and industrial arts and continued this work after his retirement.

On Sailing Around Cape Horn Alone

Cape Horn, seen from a Chilean Navy station. Wikipedia

Column: Worse Than Riding a Daggerhorn Bull

Publication date: Oct. 12, 1977

Murray’s words: Consider, historically, the five worst places in the world of sport and you might come up with (1) the five-yard line of the Chicago Bears (2) center ring with Dempsey (3) at bat with the count 0-and-2 against Koufax (4) across the net from Bill Tilden at set point (5) aboard a daggerhorn bull that had just stomped its last 11 rodeo riders.

But all of them are pale by comparison to being alone in a 40-foot boat at the bottom of a roiling sea in the Roaring 40s latitude of the South Pacific. Mean Joe Greene is a pussycat compared to Cape Horn even on a summer’s day. Koufax was just a junk pitcher compared to the South Atlantic in a gale. A Force 10 gale makes Dempsey look like a jabber. Riding a bull is like riding a rocking horse compared to riding a leaky sloop in a hurricane.

Bottom line: All Webb Chiles wanted to do was “circumnavigate the globe single-handed.”

He had failed in his first two attempts when Murray profiled him in 1977. But never doubt anyone who wants to live an epic life.

Today, Chiles is 77 and has circumnavigated the globe five times and long ago became the first American to sail around Cape Horn alone.

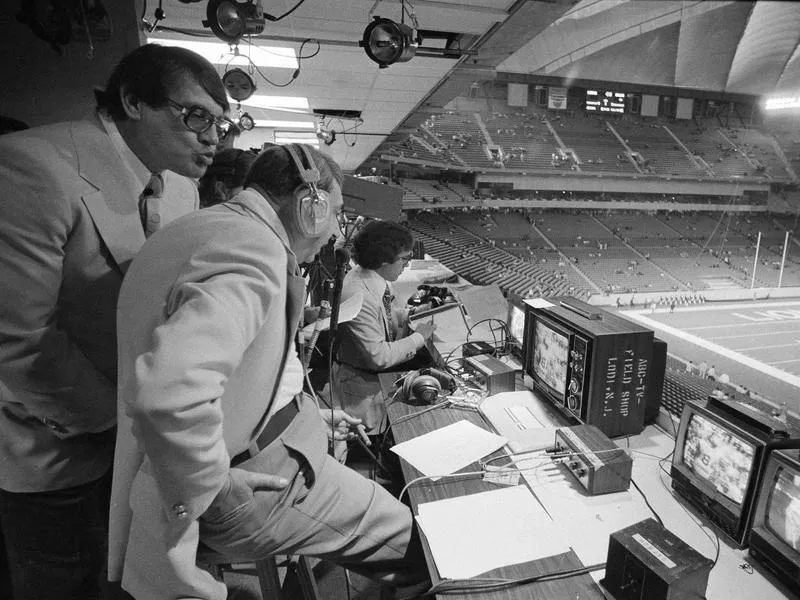

On Alex Karras’ Pro Wrestling Career

Former All-Pro defensive star Alex Karras, left, hams it up in the broadcast booth as Frank Gifford and Howard Cosell, right, prepare for the 1975 home opener of the Detroit Lions at Pontiac Metropolitan Stadium. Richard Sheinwald / AP Photo

Column: An Actor on Canvas

Publication words: Dec. 15, 1977

Murray’s take: The guys in the white hats always win, but the black hats make all the money. The Lon Chaney parts are in demand. A wrestling match is part morality play and part Disney nature study, and it is beamed to the same audience. It is an acted-out comic book. It’s also kind of true to life. The good guys never lose in the end. But the bad guys get all the money.

Bottom line: Alex Karras was a four-time Pro Bowl defensive tackle with the Detroit Lions, but the pay wasn’t so good, so he supplemented his income as “Killer Karras” in the wrestling game.

The gig paid off for the entertaining stunt man, who parlayed his ring work into a successful film and television career.

Karras then got bit by the acting bug in 1966 during the filming of “Paper Lion.”

“It was the first thing in my life I really enjoyed doing — other than football,” he said.

On Losing His Eye

Jim Murray, right, in the dugout during the Dodgers’ home opening game in 1980. Los Angeles Times

Column: If Your’re Expecting One-Liners, Wait a Column

Publication date: July 1, 1979

Murray’s words: I lost an old friend the other day. He was blue eyed, impish, he cried a lot with me, laughed a lot with me, saw a great many things with me. I don’t know why he left me. Boredom, perhaps.

We read a lot of books together, we did a lot of crossword puzzles together, we saw films together. He had a pretty exciting life. He saw Babe Ruth hit a home run when we were both 12 years old. He was Willie Mays steal second base, he saw Maury Wills steal his 104th base. He saw Rocky Marciano get up. I thought he led a pretty good life.

You see, the friend I lost was my eye. My good eye. The other eye, the right one, we’ve been carrying for years. We just let him tag along like Don Quixote’s nag. It’s been a long time since he could read the number on a halfback or tell whether a ball was fair or foul or even which fighter was down.

So, one blue eye is missing and the other misses a lot.

Bottom line: Murray’s blindness did not stop him from writing or diminish his unique perspectives on sports, the world and life.

He maintained his sharp sense of humor and shared a daily helping of goodwill with everyone who read his columns.

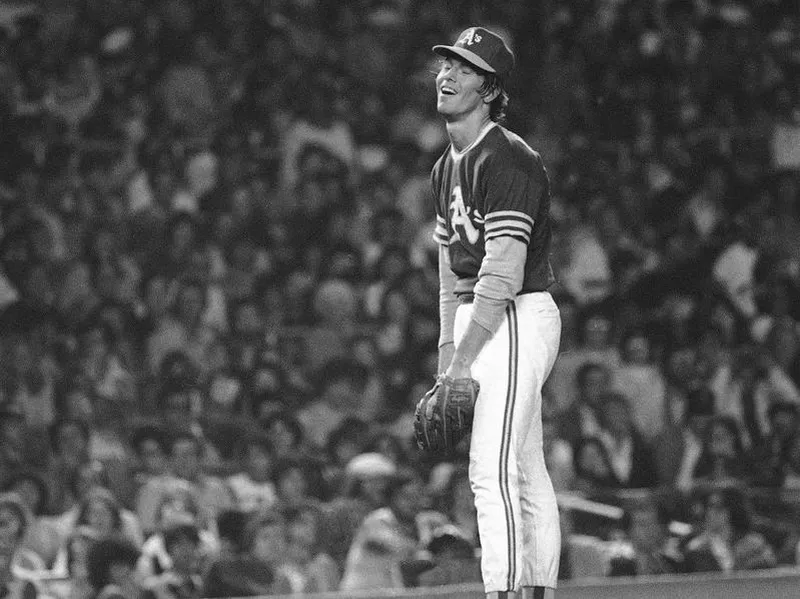

On Failure

Oakland A’s pitcher Matt Keough looks to gain some composure in a 1978 game agains the Yankees after two consecutive wild pitches scored two Yanks runs at Yankee Stadium. G. Paul Burnett / AP Photo

Column: Keough Was Best Pitcher

Publication date: April 13, 1982

Murray’s words: There’s an axiom that figures don’t lie. Well, that’s so. But they don’t always tell the truth, either. Like the rest of society, figures just don’t want to get involved. I mean, they only work here. Follow orders.

A much truer axiom in baseball is, you have to be a good pitcher to win 20 games — but you have to be a great one to lose 20.

Bottom line: Jim Murray was not big on stats. He once wrote “Babe Ruth hit about 700 home runs,” before a Los Angeles Times editor put the exact number because it “seemed kind of important.”

But Murray knew how to prove a point. Like Matt Keough had to be pretty good to go 2-17 in 1979 after starting the season with 14 straight losses.

Cy Young won 511 games, more than anybody, and lost 316 games, more than anybody. He’s wasn’t bad, either.

On Pebble Beach Golf Course

Beware of Pebble Beach. pebblebeachresorts / Instagram

Column: Pebble’s Pirates String Up Golfers

Publication date: June 19, 1982

Murray’s words: If it were human, they’d hang it from the highest yardam in the British fleet. It’s the golfing equivalent of the Spanish Main. Or the Spanish Inquisition.

These 18 holes were not cut in the picturesque countryside of Carmel Bay. They were dragged out of British prisons and shanghaied onto this hell ship. They are a classic band of cutthroats, blackguards without mercy, kindness or compassion.

Bottom line: How can something so beautiful be so treacherous?

On the U.S. No Longer Dominating in the Shot Put

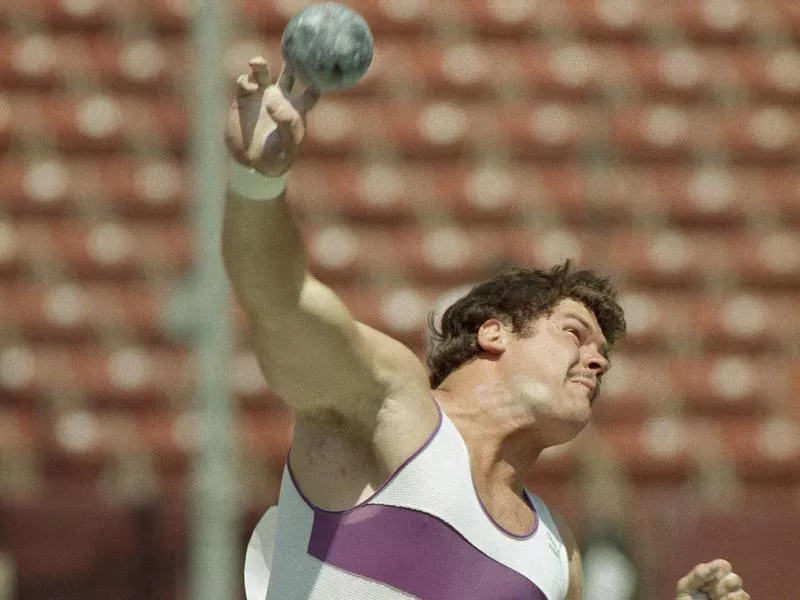

John Brenner lets fly with the shot during a qualifying round of the shot put event at the U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials in Los Angeles in 1984. AP Photo

Column: Giving His Best Shot

Publication date: May 13, 1987

Murray’s words: Lots of things that used to be uniquely American aren’t anymore. The two-door sedan, the 10-cent cigar, the clock-radio, the TV set, tires, steel, oil. Shoot! We don’t even own parts of our own cities anymore. You half expect them to have to start importing apple pie. Any day now. … You can’t win the Kentucky Derby leading an Indian pony up to the line at post time, you have to have a conditioning program … . It’s like making cars. The whole country has to chip in. Otherwise, we’re going to start having to get our shotputters the way we get most other things — off the docks. At least the shotput record should be stamped “Made in U.S.A.” again.

Bottom line: Every sport was fair game for Murray. He was a story craftsman and did not discriminate.

Give him a character or two, and he could spin a yarn for days. And inspire for a lifetime.

On Poor Coaching Decisions

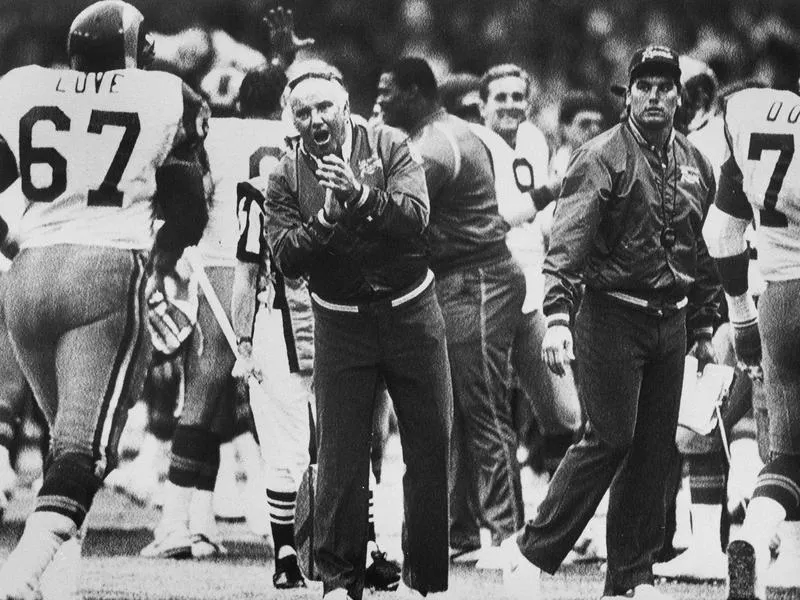

Los Angeles Rams head coach John Robinson, center, during the 1987 American Bowl in London. Doug Pizac / AP Photo

Column: Bad Calls

Publication date: Dec. 20, 1989

Murray’s words: But after the game, Ram coach John Robinson was still full of fight. “It was a good call,” he said defiantly. “It just didn’t work.”

Heroic words. He actually upgraded the call to “excellent” later and said it came “within six inches of working.”

But the notion set my colleague , Dynamite Page, and I to thinking and making a list we dubbed, “The Good Calls of History.” Such as:

1. The captain of the Titanic stood on the bridge as an officer ran up to him with a sheet of paper. “Sparks says he has a message there are icebergs coming down to starboard.” The captain smiles. “We’ll go through them. All ahead full.” Seconds later, there was a sickening crash. The captain looked down and said, “It was a good call. Six more inches and we stay up. Oh, well, you win a few, you lose a few.”

2. Of course, there was Custer. “I don’t think it’s such a good idea to go through Little Big Horn, sir,” his aide-de-camp tells him worriedly. “Nonsense!” snorted Custer. “We’ll surprise the Indians.” History records that, as he lay dying, Custer defended the move. “It was a good call,” he sighed. “Who knew the Indians would be in a zone?”

Bottom line: Accountability is in short supply sometimes in sports. Jim Murray had plenty in reserve.

He called it how he saw it — and called out whoever needed to be called out.

On Jose Canseco and Booing

Oakland A’s slugger Jose Canseco hits a home run against the Kansas City Royals in 1988, his 40th of the season. Bill Beattie / AP Photo

Column: The Man You Love to Hate

Publication date: Aug. 19, 1991

Murray’s words: The booing is easily explained. Booing is the ultimate form of respect. You only hate a thing because you fear it. They booed Pete Rose. Ty Cobb. Shoot, they were even booing Babe Ruth the day he called his shot in the ‘32 World Series. Jose Canseco is a happening. Even if he strikes out. Booing is even a form of love.

Bottom line: Is it better to be loved or feared? Jose Canseco became neither in Oakland and was traded to the Texas Rangers in 1992.

After hitting 245 home runs in his first nine years with the A’s, he hit 208 home runs over the final 11 seasons of his career with six teams.

Then, he spilled all the beans on the steroid era in an uncompromising book.

On How Jimmy Connors Changed Tennis

Jimmy Connors returns to John McEnroe in a 1977 U.S. Pro Tennis Championships match at Longwood Cricket Club in Brookline, Mass. J. Walter Green / AP Photo

Column: Connors Legend Still on Display

Publication date: Oct. 2, 1993

Murray’s words: Before Connors, the game was as genteel as tea with the Queen.The game was marked by hypocrisy. You had to wear and be white. You had to say “Yes, sir,” and “Thank you” a lot. You had to wipe your feet and take off your hat.

You got paid off in silver cups and wall plaques, so it was advisable to have independent means, not to say be downright rich. You got paid off in the dark and you never took a check. You screamed at an official, you took the next plane home.

Master Connors wasn’t having any of this. Born near what may be the toughest section of the world this side of the Marseilles waterfront, East Saint Louis, Ill., he came into the game with his fists cocked, his jaw forward and his attitude truculent. He never did anything easy in his life. He hit every ball as if it were as intruder in his bedroom at night. Babe Ruth never swung at a ball any harder than James Scott Connors.

Bottom line: Image wasn’t everything for Jimmy Connors. Winning was. He was a throwback, old school. And old school suited Jim Murray just fine.

He respected hard work and had no patience for the look-at-me sports culture:

“To begin with, I’ve had it up to here with tabloid America. The glorification of the rebel, the outlaw, the guy who makes up his own rules. And makes you live by them. You know what I’m talking about: tennis players who get famous not for their forehands but because of the one their wives plant on the jaw of tennis officials, basketball players who make millions and don’t show up for team practices and make magazine covers, scofflaws whose very criminality gives them celebrity, the whole sorry, sick panoply of sports in the ’90s.”

A hero in Murray’s book was a family man who showed up to work every day, worked 14-hour days to raise his eight children, provide for his family and make the “tools that build the country.” Like his grandfather.

On Michael Jordan’s Greatness

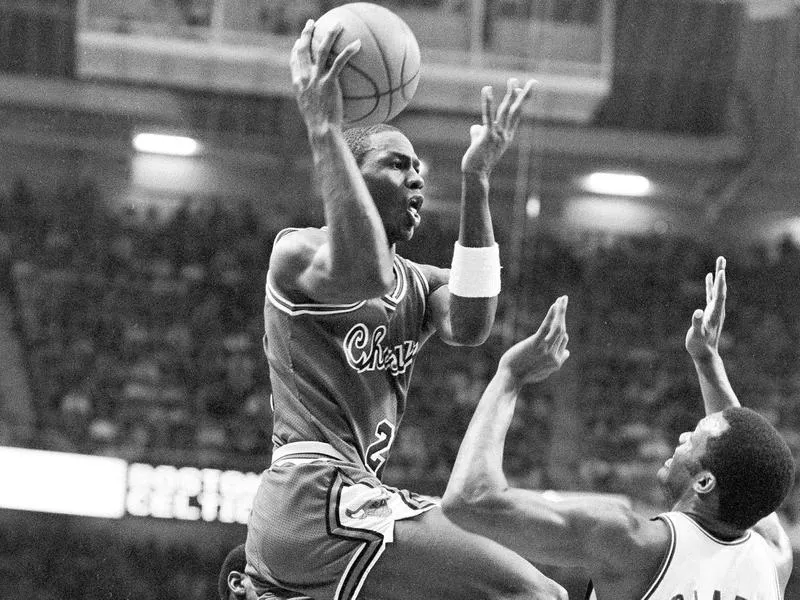

Chicago Bulls Michael Jordan goes up for two against the Boston Celtics at the Boston Garden in 1985. Amy Sweeney / AP Photo

Column: All the NBA World Was a Stage for This Player

Publication date: Feb. 4, 1996

Murray’s words: You go to see Michael Jordan play basketball for the same reason you went to see Astaire dance, Olivier act or the sun set over Canada. It’s art. It should be painted, not photographed.

It’s not a game, it’s a recital. He’s not merely a player, he’s a virtuoso. Heifetz with a violin. Horowitz at the piano. … What he’s doing is making a shambles of the game of basketball, laying waste to the landscape. He’s as unstoppable as tomorrow.

Bottom line: Why do you think everyone wanted to “Be Like Mike”? Many people still do.

Murray’s wrote this 1996 column after a Chicago Bulls win over Magic Johnson and the Lakers, and like Michael Jordan’s legacy, the words have aged well.

On Mike Tyson Biting Evander Holyfield

Mike Tyson bites into the ear of Evander Holyfield in the third round of their 1997 WBA heavyweight match in Las Vegas. Jack Smit / AP Photo

Column: Tyson’s a Two-Bit Fighter

Publication date: June 29, 1997

Murray’s words: It was such a shocking bit of cannibalism, they decided to halt the proceedings before Tyson tried to put him in a pot. I guess people in the dawn of history settled matters that way. But today only dogs and mosquitoes get forgiven for biting. Prizefighting has rules. No kicking, choking, shooting, knifing—or biting.

Bottom line: Jim Murray never pulled any punches. He once celebrated Tyson as one of the most dangerous men to ever step in a ring: “When Mike Tyson gets mad, you don’t need a referee, you need a priest.”

But few athletes fell farther, faster, than Tyson — whose meteoric rise to the pinnacle of boxing and stunning fall from grace were legendary.

The boxer transformed himself into a redeeming character in his post-fighting life. That deserves respect and is part of the human struggle of sports Murray captured better than anyone.

On Winning

Jockey Chris McCarron approaches the wire and the win atop Free House, right, in the 1999 San Antonio Handicap at Santa Anita Park in Arcadia, Calif. John Hayes / AP Photo

Column: You Can Teach a Horse New Tricks

Publication date: Aug. 16, 1998

Murray’s words: The Bridesmaid finally caught the bouquet. The best friend got the girl in the Warner Bros. Movie for a change. The sidekick saves the fort. … It’s a very big win for Free House. He’s not What’s-His-Name anymore. He’s Who’s Who.

You know, in most sports, the athlete gets a generation to prove himself. A Jack Nicklaus wins his first major at 22 and his last at 46. A George Foreman wins Olympic boxing gold in 1968, and 30 years later he’s still fighting. Babe Ruth hits his first home run in 1915 and his last in 1935.

But a racehorse has to act like he’s double-parked. He gets only months to prove he has been here.

Bottom line: Jim Murray loved the races. And the races loved him back. He went out with his fastball blazing in this column, his final one.

The day after writing these words, Murray died of a heart attack at his home. He was 78.

Somewhere, he’s still wisecracking.

You can read more Jim Murray columns here.