Like Muhammad Ali, tennis great Arthur Ashe stands as one of those transformative sports figures whose impact off the court — or in Ali’s case, outside the ring — rivals or surpasses his athletic feats.

At the same time, it would be difficult to find two athletic greats who were more different from one another than Ali and Ashe. Aside from the fact they both achieved stardom as African-American sports icons during the turbulent civil rights years of the 1960s, they could not have been more opposite in demeanor and temperament.

In 2016, President Barack Obama made that point when he spoke of Ashe and Ali being the sports figures he most admired, perhaps the most fitting tribute to their contrasting personalities and ability to achieve transformational ends through such different means.

Where Ali was the brash motormouth who seemingly never let a thought go unspoken, Ashe often played the role of soft-spoken, reserved diplomat. Where Ali boasted of his greatness, Ashe was the picture of humility on and off the court. And where Ali plunged headfirst into the great social debates of his day, Ashe was more judicious in picking his spots to speak out while always leading through an example marked by dignity and civility.

It’s all the more surprising, then, that Ashe and Ali were the bookends of an era where black athletes found their voice and and led the charge for social justice on so many fronts.

Here are 24 incredible facts about Ashe that help explain his legacy on and off the court.

A Man of Firsts

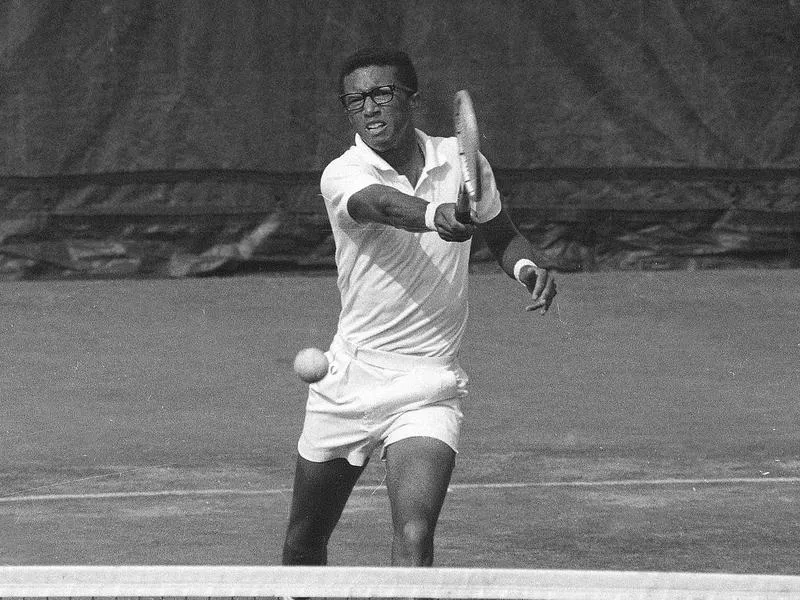

Arthur Ashe hits a return to Tom Okker in the 1968 U.S. Open men’s singles final at Forest Hills in Queens, N.Y. Ashe won the title in five sets, 14-12, 5-7, 6-3, 3-6, 6-3. Marty Lederhandler / AP Photo

It’s no exaggeration to say Ashe was the Jackie Robinson of men’s tennis. He broke no shortage of color barriers, becoming the first African-American to join the U.S. Davis Cup team, and later becoming the first — and still only — African-American to win U.S. Open, Australian Open and Wimbledon championships.

A few days after winning the U.S. Open in 1968, he became the first athlete to appear on the CBS public affairs program “Face the Nation.”

In 1985, he became the first African-American man to be inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

Overcoming Racism on the Court

Arthur Ashe, right, and Hubert Easton, second from right, shake hands with their opponents, John Botts, left, and Herbert Gibson, before their match in the Eastern Junior Tennis Championships at Forest Hills in Queens, N.Y., in 1959. Harry Harris / AP Photo

Sometimes mistaken for a water boy or waiter while playing tournaments in the country club sport of tennis, Ashe was no stranger to racism as an African-American sports pioneer.

In 1969, a year after winning the U.S. Open, Ashe was ordered off the tennis court at an all-white Florida club.

Mentored by the Two Panchos

Pancho Gonzales lost to Arthur Ashe in the fourth round of the men’s singles championships at Wimbledon in 1969. AP Photo

Tennis greats Pancho Gonzales and Pancho Segura both took notice of a young Ashe while he was attending UCLA, and played key roles in helping to refine his tennis game.

It certainly seemed to help, as Ashe won the NCAA men’s singles and doubles championships in 1965, while also leading the Bruins to the team title.

Ashe and Gonzales would face off twice in 1969, splitting their meetings at Las Vegas (Gonzales victory) and Wimbledon (Ashe victory).

Ashe beat Segura in their only meeting, in 1970 in Los Angeles.

He Was Once Accused of Being an Uncle Tom

Arthur Ashe, left, talks with Chairman Charles C. Diggs, D-Mich., of the House Foreign Affairs subcommittee on Africa in 1970. Ashe was denied a visa by South Africa, compelling hearings “to probe the foreign implications of a black American having his visa denied,” said Diggs. Bob Daugherty / AP Photo

Ashe’s quiet demeanor and nonconfrontational approach toward social justice didn’t always endear him with activists during the civil rights era, when African-American athletes like Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Bill Russell tended to be more outspoken.

Ashe addressed the issue head-on when he said: “Sometimes a demonstration is the best way of getting headlines about a bad deal, but I don’t think demonstrators should try to make trouble for anyone. We’ll never advance very far by force, because we’re outnumbered 10 to 1. Quiet negotiation and slow infiltration look more hopeful to me. Does this make me an Uncle Tom? If so, OK.”

He Shocked the Tennis World Again in 1975

Arthur Ashe, right, shakes hands with Jimmy Connors after winning the 1975 men’s singles title at Wimbledon. Connors was the 1974 Wimbledon champion. AP Photo

Despite the years he had spent as a top-ranked player, Ashe entered the 1975 Wimbledon tournament again as a decided underdog, much as he had been at the U.S. Open seven years earlier.

Defending champion Jimmy Connors was the heavy favorite, and a young Bjorn Borg also loomed.

Despite having lost his three previous meetings with Connors and appearing past his prime at age 32, Ashe pulled off the upset in the final, defeating Connors in four sets.

He Played Tennis While Serving in the Army

Arthur Ashe, a 25-year-old Army lieutenant stationed at West Point, beat Bob Lutz of USC to become the first African-American to win the U.S. men’s singles title in the 88th National Tennis Championships at Longwood in Brookline, Mass., on Aug. 25, 1968. AP Photo

Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be inducted into the Army was a signature chapter in his life and boxing career. Ashe, on the other hand, spent three years in the Army after graduating from UCLA in 1966, even as he continued to excel on the court.

Indeed, he still was in the midst of his military service when he won the U.S. Open in 1968.